Milena Kostić

SUBJECTIVITY AND INTERSUBJECTIVITY IN DISCOURSE ON THE TOPIC OF GLOBAL BUSINESS

Abstract: In this paper we observed examples of subjective and intersubjective modality with the aim to explore how they are realized in the discourse of global business and find out whether speakers express their opinion openly or tend to share the responsibility. We analyzed modal expressions such as modal adjectives, modal adverbs, mental state predicates and modal auxiliaries in the corpus consisting of five interviews. In the analysis of our corpus data we relied on the model proposed by Jan Nuyts in his book Epistemic Modality, Language, and Conceptualization. The expectations were that the speakers will predominantly use intersubjective expressions and will try to share the responsibility with others. However, the analysis revealed that speakers expressed their opinions subjectively. There were 258 instances of subjective modal expressions and 68 instances of intersubjective modal expressions. However, modal auxiliaries prevail in the corpus which suggests that speakers are somewhat tentative and leave room for other interpretations of their utterances.

Key words: subjective and intersubjective modality, modal auxiliaries, modal adjectives, modal adverbs, mental state predicates

- 1. Introduction

This paper deals with the concepts of subjectivity and intersubjectivity and attempts to explore how they are realized in the discourse of global business. The topic of global business is contemporary and all-pervasive. However, it is very demanding in terms of explicating one’s point of view about the current economic situation which is changing rapidly. Therefore, one can never be sure that their opinion will be relevant in the near future. What we will try to explore in this paper is how the opinions, predictions or guesses about the situations in the sphere of business are voiced. The question we will deal with is whether they are expressed as explicitly subjective or as overly intersubjective. Should intersubjectivity prevail, it will signal that speakers prefer to share responsibility.

This paper is structured in the following way. The first part is a theoretical background in which we first present the model used in the analysis. This model is proposed by Jan Nuyts and it focuses on the distinction between subjectivity and intersubjectivity. Then, we review the definitions of the terms subjective and objective modality with the aim to outline the features of subjective modality. Benveniste, Lyons and Verstraete’s views on this notion are considered. The third part of the paper focuses on the description of the corpus-based approach to data analysis and outlines the features of the corpus. The fourth part is data analysis and the presentation of results. Finally, we draw conclusions based on the results and propose issues for potential future research.

- 2. Theoretical background

2.1. The model used in the analysis

In the analysis of intersubjective and subjective modality in the corpus data, we will rely on the model that is proposed by Nuyts in his paper on subjectivity and its role in epistemic modal expressions and in his book Epistemic Modality, Language, and Conceptualization. We assume our corpus will abound in epistemic modality. Moreover, we include deontic modality in the analysis as some instances are likely to appear in the corpus.

As regards the definition of subjectivity, Nuyts (2001a: 384) explains that the most representative one is Lyons’, in which he says that subjectivity is associated with the presence of the speaker in the utterance.

Nuyts (2001a: 384,385) explains that subjective epistemic modality can be expressed performatively which means that when the speaker uses a certain modal expression, they accept full responsibility for the utterance at the moment of speaking. This is in contrast with the descriptive use of subjective epistemic modality “in which the speaker reports on someone else’s epistemic evaluation of a state of affairs without there being any explicit indication as to whether the speaker personally subscribes (i.e. is committed) to the veracity of the evaluation or not” (Nuyts 2001a: 385). Nuyts (2001b: 40) points out that deontic modality can also have a performative dimension.

“Without any evidence one cannot evaluate the probability of the state of affairs” (Nuyts 2001b: 34). Nuyts makes the reader realize that epistemic modality is based on some kind of evidence. The evidence can be a physical object, a concrete item or also knowledge about a certain situation. Additionally, Nuyts (2001a: 386) points out that one has to bear in mind the quality of the evidence and/or nature of the evidence which are important for making an epistemic judgement.

These are the two dimensions which we will observe in the analysis. First, there is “the speaker’s evaluation of the probability of the state of affairs, i.e. the epistemic qualification” (Nuyts 2001b: 35). Secondly, “there is his/her characterization of the status or quality of the sources (evidence) for that qualification” (Nuyts 2001b: 35) which belongs to evidentiality. Nuyts (2001a: 386) argues that these two dimensions represent an interaction of epistemic modality and evidentiality. With regard to this, he suggests that we should refer to it as “subjectivity and intersubjective evidentiality” (Nuyts: 2001b: 35). Nuyts (2001b: 36) further explains that the dimension of (inter)subjectivity can also apply to deontic modality which was first pointed out by Lyons (1977).

When it comes to the linguistic reflection of the dimension of subjectivity, Nuyts (2001b: 29) has observed epistemic modal adverbs, modal adjectives, mental state predicates and modal auxiliaries. He concluded that some of them typically have the dimension of subjectivity and some of them do not. He calls the latter group ‘non-subjective’ rather than ‘objective’.

As for modal adverbs, Nuyts (2001a: 389) suggests that they are neutral regarding the dimension of subjectivity. Depending on the context they may be subjective or non-subjective. As regards modal adjectives, Nuyts (2001a: 389) points out that they express non-subjectivity which is signaled by their impersonal form. Therefore, modal adjectives are typically intersubjective. However, no matter how intersubjective they are, Nuyts (2001a: 390) adds that when the speaker enters the scene in the discourse, the utterance immediately turns subjective. Mental state predicates are subjectively modalized. They normally occur in contexts in which “the speaker voices his personal opinion very often about topics in the realm of strictly individual experiences or concerns, or also in contexts involving antagonism between the views of speaker and hearer” (Nuyts 2001a: 390,391). As mental state predicates are voicing tentative, personal opinions, they can be used as hedges. This implies that speaker is “officially leaving room for another opinion or for a reaction on the part of speaker” (Nuyts 2001a: 391). Regarding modal auxiliaries, Nuyts (2001a: 392) suggests that whether they will have the dimension of subjectivity or non-subjectivity depends on the context. In that sense, they are very similar to modal adverbs.

In Nuyts’ definition of subjectivity, the other pole of this dimension is not objectivity but intersubjectivity, which will as such be used in the analysis of corpus data. We refer to it as equal to non-objectivity. Moreover, the notion of evidentiality is added to it. Therefore, subjectivity “involves the speaker’s indication that (s)he alone knows (or has access to) the evidence and draws conclusions from it”, whereas intersubjectivity “involves his/her indication that the evidence is known to (or accessible by) a larger group of people who share the same conclusion based on it” (Nuyts 2001a: 393). We conclude that in the first case, the speaker is the only one who is responsible for an epistemic qualification, whereas in the second, the responsibility is shared by a group of people who are familiar with the evidence. Nuyts (2001a: 394) explains his preference for the poles subjectivity/intersubjectivity in his analysis by pointing out that objectivity can also be observed in the interviews he analyzed, but what seems to be the objective stance in that kind of discourse is actually shared by a larger group of people, including the speaker and the interaction partner. That is why it is more reasonable to call it intersubjective rather than objective. Also, subjectivity is related to “formulating the hypothesis ‘on the spot’”, whereas in intersubjectivity “the information (and the epistemic evaluation of it) is generally known, and hence is not new (or surprising) to speaker and hearer(s)” (Nuyts 2001a: 396).

All mentioned aspects will be included in the analysis of our corpus data. Additionally, Nuyts (2001b: 41), in his analysis, includes information structure of modal expressions, which refers to the importance of certain parts of information in a sentence. This aspect remains unaddressed in the present paper, due to the complexity of the analysis. Nevertheless, it can be a proposal for future research. Discourse strategy is also observed in Nuyts’ analysis (2001b: 44) because it reflects an interpersonal relationship with the listener/reader. This aspect will be considered in the present paper, yet briefly.

This was the description of the model that we will use in the analysis of our corpus data. However, we have to point out that there are other views on subjectivity and intersubjectivity and also on modality and evidentiality.

Elizabeth Traugott (2010: 1) defines the notion of subjectivity as “a relationship to the speaker and the speaker’s beliefs and attitudes” whereas intersubjectivity is “a relationship to the addressee and addressee’s face”. She doesn’t include context as one of the factors that can influence this dimension, which is obviously in contrast with Nuyts’ definitions of these notions. Bеrt Cornille has a somewhat different view compared to that of Nuyts’ regarding the categories of epistemic modality and evidentiality. He (Cornille 2009: 44,58) describes them as separate, although he points out that they have the dimension of reliability of evidence in common. Cornille (2009: 48) suggests that “inferential evidentiality is regarded as an overlap category between modality and evidentiality”. According to him there are three types of inferences: “circumstantial, generic and conjectured” (Cornille 2009: 50,51). However, in this paper we will not be dealing with them explicitly. We believe that one cannot make a clear-cut distinction between the categories of epistemic modality and evidentiality and that at some point they have to merge.

To sum up, in the analysis we will be dealing with modal expressions which can express subjective epistemic and deontic modality and intersubjective evidentiality as defined by Nuyts. We will attempt to explain in what contexts they are frequently used and to outline the implications of this use. We would like to answer two questions in the analysis: 1) Is the speakers’ involvement in (or commitment to) the proposition more often subjective or more often intersubjective? 2) In what situations do speakers prefer to share the responsibility with the group?

2.2. Subjective and objective modality

Benveniste was the first author who introduced the notion of subjectivity in language in 1971. “Language is possible only because each speaker sets himself up as a subject by referring to himself as I in the discourse” (Benveniste 1971: 224). This definition helped many authors to grasp and further elaborate on subjectivity. He also introduced the notion of intersubjectivity, which makes the communication between, at least two, people possible.

When making a distinction between subjective and objective modality, authors have referred to the connection of the speaker with the utterance. Lyons (1977) explains that the notion of subjective modality has always been associated with the presence of the speaker in the utterance and the notion of objective modality has been associated with the content of the proposition. Verstraete (2001: 1506) agrees that “the issue of speaker-relatedness in modality has traditionally been discussed in terms of the distinction between subjective and objective modality”. More importantly, Verstraete (2001: 1510,1511) adds that modality can also be interpreted in terms of the notion of evidentiality.This is especially true for epistemic modality. He agrees with Nuyts that, when talking about subjective modality, one should also bear in mind performativity.

Verstraete (2001: 1518) concludes that epistemic modality is typically subjective and deontic modality can be both subjective and objective. Subjective deontic modality exhibits similar properties as subjective epistemic modality.

- 3. Corpus

In the analysis we will use a corpus consisting of 5 randomly selected transcripts of interviews on the topic of global business. The podcasts with interviews were downloaded from the BBC World Service website. The host interviewer is Peter Day who is a renowned presenter on the BBC radio. He interviews people from around the world with whom he discusses current issues in global economy and the business world. Each podcast lasts approximately 28 minutes. The transcript mostly consists of the target language and it is 20 pages long. We had to include the co-text as the context in which the utterance is spoken will be important and it will probably influence the analysis as was already outlined. We have to be aware of the fact that, “corpus data do have their limits, as they are vulnerable to purely accidental gaps. The larger one’s corpus, the smaller this risk. But there are limits to the amounts of corpus data one can reasonably process if they are to be analyzed in-depth” (Nuyts 2001b: 46). In the following section we will examine the examples from the corpus.

- 4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Modal Adjectives

Modal adjectives are typically characterized as intersubjective but they can also be subjective. They are the least prominent modal expression in this corpus as there are only 9 instances of certain, possible, probable and its alternative likely in all 5 transcripts. The modal adjective clear has an evidential dimension and it is rather termed evidential than epistemic.

Now, we will examine examples from the corpus which involve intersubjectivity.

1…This week three experts predict what is likely to be on our mind in 2013.

This is an intersubjectively based evaluation and the modal qualification is the property of the state of affairs (following Nuyts 2001b: 67). It also involves evidentiality. This is an inference from available knowledge and common sense reasoning. One can infer that the speaker belongs to the group which has the access to the evidence and he/she is sharing the responsibility with the group.

Modal adjectives can also involve subjectivity. Nuyts (2001a: 390) explains that the moment the speaker enters the scene, i.e. becomes explicit in the utterance, in the form of a personal pronoun, it becomes subjective which is illustrated by the following example:

2… I guess I am. I don’t think it would be possible for governments to maintain the kinds of secrets they have maintained…

“The presence of subjectivity is also inevitable in expressions containing modal adjectives that express certainty as in I am sure (of it) (that …)” (Nuyts 2001b: 68). We have identified 3 such examples in the corpus one of which is:

3… I would remind you of something which I am sure you already know which is that the Japanese government borrows tenure money…

This is an example of epistemic modality and it has a dimension of evidentiality. The evidence is publicly available and the speaker unambiguously voices his opinion. There were no instances of deontic modal adjectives in the corpus.

These modal adjectives have a dimension of performativity, as all of them are epistemic. They express the commitment of the speaker to the utterance.

When it comes to the implications of such uses of epistemic modal adjectives, Nuyts (2001b: 101-103) explains that it is very difficult to spot a discourse strategy that a speaker is intending to use. However, he states that even if any strategy is employed it is not there to mislead the hearer or the interlocutor.

Regarding this small number of examples of modal adjectives, we conclude there are more instances of subjective epistemic modality and more performative uses of epistemic modality. This could imply that the speakers are expressing their opinion openly without trying to share the responsibility with the group. This is contrary to the expectations outlined in the theoretical background, but we will see in the following sections that subjective examples are actually predominant in this corpus. However, this conclusion should be checked on a much bigger corpus.

4.2. Modal Adverbs

Modal adverbs can either be subjective or intersubjective depending on the context in which they occur. The modal adverbs that we analyzed in the corpus are: certainly (undoubtedly and surely), probably, possibly (maybe and perhaps). Nuyts (2001b: 56) points out that seemingly, apparently and clearly are classified as evidential, whereas presumably is both epistemic and evidential, but there are no instances of presumably in the corpus. We will start with certainly and its subjective and intersubjective realizations.

There are 11 instances of this modal adverb in the corpus, 7 of which express intersubjectivity and 4 of which express subjectivity. Due to their form, modal adverbs seem to be predisposed to express subjectivity, but in the end it depends on the context. In this type of discourse, it is not surprising that modal adverbs are used intersubjectively, because in that way, the speaker is less responsible for the utterance he makes, as in:

4 …The truth of the fact is that certainly, from my company’s perspective, we are learning as much from the people that…

Here, the speaker obviously stands together with the co-workers and expresses an opinion they all share, signaled by the context following the adverb. However, certainly can express a purely subjective stance, as in:

5…I think you can certainly argue that the world is becoming more complex and a bit more competitive.

This implies that the speaker does not share his opinion with the group and he/she accepts all the consequences for the utterance. The adverb surely, the alternative of certainly, can be spotted in two sentences in the corpus, both of them being intersubjective. In such examples, the speaker is voicing his opinion on the basis of a well-known situation with which the larger group of people is familiar. These examples suggest the expected outcome in the discourse on

global business. People rather express the facts that are known to a larger group of people, as in that way the utterances are less prone to criticism.

Another modal adverb is probably. There are 8 instances of it in the corpus, 5 of which are subjective and 3 of which are intersubjective. This is slightly different when compared to certainly. A representative subjective use is illustrated in:

6 …I think probably the latter, they are learning. Competition is something which, certainly in our experience makes a business better…

This example clearly represents the speaker’s opinion, as he is emphasizing that he has reached the conclusion. On the other hand, the instances of intersubjectivity imply that the situation and inferences the speaker draws from it, which are publicly available and easy to spot, can be shared by a group of people:

7…That’s it, if you don’t know about queue arc codes… you probably do know about them because that is little square bar-codish type looking thing…

The next modal adverb is possibly, and there is only 1 occurrence of it in the corpus which is used subjectively. However, there are more instances of maybe and perhaps, which are the alternative forms of possibly. There are 3 intersubjective and 2 subjective instances of maybe, and there are 2 subjective and 2 intersubjective instances of perhaps. In the following example we present the intersubjective use of the modal maybe :

8…Well, the number of children per couple is maybe a different issue. The anecdotal evidence is that most people in Japan get married and most people who get married want to have two children.

This opinion is shared as the evidence for its existence is available to anyone living in Japan and witnessing the current state of affairs.

Now we will briefly turn to the examples from the corpus that involve evidentiality. There are 6 such instances, 3 of which are realized in the modal adverb clearly, and the rest of them are found in examples with supposedly and seemingly. For the purpose of illustration we present here one such example:

9…One of the things that we see clearly is that these companies are establishing themselves not through advertising but rather…

The other two also suggest that the evidence is known to the group of people including the speaker. In all of these instances, the speaker is familiar with the evidence as is the larger group of people and they share the responsibility.

As regards performativity, all instances of modal adverbs are used performatively. This means that speakers are committed to the stance they explicate in the utterances. There are no descriptive uses of modal adverbs. They cannot be used descriptively, unless they are part of reported speech, but there were no such instances in this corpus. There were also no instances of deontic modal adverbs. As for the discourse strategy, the same applies here as to the modal adjectives, i.e. there is no hidden meaning behind the use of modal adverbs in discourse on the topic of global business. The only prominent conclusion that comes to our attention is that, in modal adverbs there are slightly more instances of intersubjective uses, namely 17, 14 instances of subjective uses, and 6 instances of evidentiality which could imply that the speakers prefer to voice opinions which are shared by a group of people and to talk about the things for which they have some kind of evidence that is also publicly available.

4.3. Mental State Predicates

The most representative members of the category of mental state predicates are think and believe, and then doubt, know, suppose and guess. Nuyts (2001b: 108-110) points out that the verb think is the most prototypical member in the category. On the epistemic scale, “know is clearly stronger than think […] and doubt refers to the negative side of the scale. The difference between think, believe, suppose and guess is quite vague regarding the strength of the qualification expressed: they simply indicate that it is somewhere on the positive side of the epistemic scale” (Nuyts 2001b: 110,111). All of these verbs include an evidential dimension. “The evidential dimension of predicates such as know, guess or suppose may be more dominant than that of think or believe. Think and believe are epistemic predicates, albeit not only or not purely epistemic ones, but mixed epistemic evidential ones” (Nuyts 2001b: 113). Both verbs express subjectivity, which implies speaker’s responsibility for the information in the utterance. As we will see in the corpus, these verbs especially occur in debates and interviews, “as a speaker is frequently forced to produce opinions on the spot and to formulate immediate and unprepared reactions, which are therefore often tentative, impressionistic and personal” (Nuyts 2001b: 123). “The use of the mental state predicate leaves no doubt about who is responsible for the epistemic evaluation” (Nuyts 2001b: 123).

Doubt is the only mental state predicate that does not appear in the corpus. The most frequent and prominent one is think, which is followed by know. There are only several instances of believe, suppose and guess.

We will begin with the analysis of the verb think. Its most frequent use is subjective and there are 81 instances of it in the corpus. The majority of them are based on some kind of evidence which can be inferred from the context. The most frequent instance of think is in the form I think as in the example:

10…I think as far as business is concerned, the smarter companies are already there.

This implies that the speaker is taking the full responsibility for what they are saying. As there is an evidential dimension in this verb, we can conclude that the speaker is not just randomly expressing their opinion but actually supporting it. There are also some intersubjective instances of the verb think, in which we see that the speaker’s opinion is shared by a group of people. There are 5 such examples in the corpus, the most representative one being:

11…we are also seeing something really radical happen with the way we think about the machine…

The next mental predicate is know. Altogether, there are 20 instances of know in which the verb is used either as subjective or intersubjective. There are 9 instances of subjective use, as shown in the example:

12… I know it is difficult to predict things especially about the future.

This number of occurrences suggests that the speakers are not that willing to express their opinion with the strongest mental predicate, which either implies their uncertainty or avoidance of responsibility. The dimension of evidentiality is present in all instances. As for the intersubjective use, there are 11 examples, especially in the second transcript in the corpus called “2013 Look Ahead”:

13… Multitasking slows you down and makes you make more errors, we know that. We also know that when you are short of sleep, that means less than six hours a night, your cognitive functioning is impaired at the same level as if you were drunk.

The speaker wants to emphasize that the evidence is shared by a group of people to which both the speaker and the interlocutor belong. The evidence is available from experience. In that way, the speaker shares the responsibility for what she utters. This is an exception in the corpus, but it shows that when someone is making a suggestion (inferred from the wider context) which might be easily criticized, they continuously use intersubjectivity, because in that way they stay on the safe side.

The examples of suppose, guess and believe are not prominent in the corpus. Altogether, there are 10 of them: 6 suppose, 2 guess and 2 believe.

All instances of suppose are without doubt used subjectively as in:

14…And that is about the return, I suppose, you might call it the return of manufacturing to develop markets…

Both instances of guess are used in the same way and both of them have a more or less obvious dimension of evidentiality in them which supports the speakers’ subjective opinion. As for believe, 2 instances that we find in the corpus are rather intersubjective which indicates that the speaker is sharing responsibility with a group of people.

As for the dimension of performativity, one can notice that the performative use prevails in the corpus due to the speakers’ commitment to the propositions. However, there are 10 descriptive uses of the mental predicate think, 3 examples of know and only 1 example of believe. Descriptive use is illustrated in:

15… Most people think that a falling of population is a problem for Japan.

To sum up, this predominant use of mental state predicates implies that the speakers are not constricting themselves when it comes to voicing personal opinions. The most numerous examples of think, which is definitely weaker than know, may imply that “the speaker is saying tentative things about which (s)he may actually be wrong. Thus the predicate weakens or mitigates the force of the claim or the reaction, in such a way that it does not endanger the conversation and leaves room for intervention by the interaction partner” (Nuyts 2001b: 165).

4.4. Modal Auxiliaries

The system of English modal auxiliaries consists of central and marginal modal verbs. Central modal auxiliaries are can, could, may, might, shall, should, will, would and must. Marginal are dare, need, ought to and used to. These modals can express three types of modality: epistemic, deontic and dynamic. However, it is not always easy to determine, what modality they express. Very often they can express two modalities at the same time. This is especially true for modals such as can and will. We will be observing epistemic and deontic modality in the corpus, as they are marked with the dimension of subjectivity and non-subjectivity. As for dynamic modality, it will not be considered in this analysis because it is “fully ‘agent-oriented’, whereas epistemic modality is fully ‘speaker-oriented’” (Nuyts 2001b: 193). Deontic modality, in this respect, is somewhere in between.

When it comes to determining subjectivity or intersubjectivity of the modal auxiliaries, we observed the context in which they were situated in the text, whether the evidence is accessible to a group of people and/or a speaker and how that is expressed. In the whole corpus there are 120 instances of subjective epistemic and 20 instances of subjective deontic modality, 12 instances of intersubjective modality, 6 of which are epistemic and 6 of which are deontic. This implies that the speakers are obviously explicitly expressing their opinions. Among these 120 examples of subjective epistemic modality there are 12 examples which are somewhere between epistemic and dynamic modality, the so-called ambiguous examples which cannot be clearly defined from the context. Clearly defined examples of subjective epistemic modality of modal verbs are various. There are 22 examples of the so-called real epistemic modal verbs, 15 of which are with may and 7 of which are with might. This implies that the speakers in this type of discourse are not prone to speculating and they are even less prone to deducing. There is one instance of subjective epistemic must, which is shown in the following example:

16…Something must be going on somewhere if these official economic figures are right.

In the discourse of global business, speakers prefer making assumptions with will and would. That is why these two auxiliaries are the most numerous in the corpus:

17. … You will have everybody aiming too low….

18. …There’s a sort of back and forth and I would say…

Regarding intersubjective epistemic modality, we came across 6 examples in the corpus one of which is:

19. We can all get worried or interested or whatever it might be about so-called rising businesses emerging markets, whatever we are gonna call them…

The speaker is explaining what can possibly happen, but he is not presenting this as if it were only his opinion, but rather the opinion of a group of people, actually of all people.

As for subjective deontic modality, there were significantly less instances than for epistemic modality. There were 20 instances in the whole corpus, one of which is:

20. …and I think there really needs to be a downsizing of government of the country which nobody seems to be thinking seriously about …

Here, the speaker is obviously expressing his opinion about the state of affairs.

As regards intersubjective deontic modality, there were 6 such instances in the corpus, one of which is:

21. … we really need to rethink how do we play in that world in a completely different business model…

Here the speaker, a university professor, is suggesting what has to be done, and it is the authorities who should deal with this. He is making the utterance intersubjective by putting himself in the same group with them in order to make his suggestion less intrusive.

The prevailing use of subjective modal auxiliaries in the corpus suggests that the speakers, while answering the interviewer’s questions on the topic of global business, are rather estimating the state of affairs than giving explicit, firm opinions, which is to a certain extent predictable. As Nuyts (2001b: 225) suggests, the reason for this could be that “these modals are sometimes used to indicate that although the speaker does not (want to) or cannot reject a suggestion by the interlocutor, (s)he does not want to endorse it either”.

This was the overview of all the modal expressions that we found in the corpus and the overview of implications they may have. In the following section, we will summarize the results of the analysis.

- 4. Conclusion

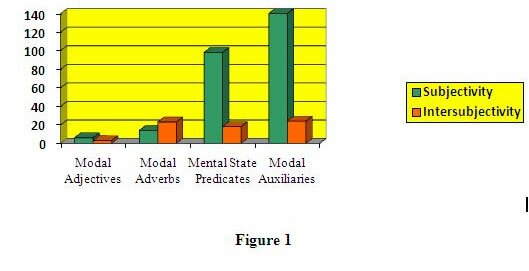

In order to have a clear picture, literally, of what the results of the analysis imply, we will present them in a form of a chart, which is shown in Figure 1.

One can infer from the above chart that examples of subjectivity predominate in the corpus on the topic of global business. The result has turned out to be in opposition to what was expected, which is that the instances of intersubjectivity will prevail in the corpus. The implication is that when the experts talk about economy and potential growth and development of a country, they express their personal opinion and do not try to share the responsibility with the group. However, we have to observe these results with caution, as there were many instances of the personal pronoun “we” in the corpus, which we didn’t take into consideration in this analysis but it could signal that, even though the modal expressions are predominantly subjective, there could be some other linguistic expressions as this one that indicate intersubjectivity. Be that as it may, this analysis implies that subjectivity is the main characteristic of this type of discourse and that it is mainly expressed via epistemic modality. As the most numerous cases are modal auxiliaries which are rather tentative, this could imply that speakers are not categorical and that they leave room for other interpretations. These results can certainly be checked on a much bigger corpus of data and other non-modal expressions could be included in that analysis, too. In addition to that, the proposal for further research could be to use Iwamato’s model of points of view and different modal features (Iwamato 1998) to analyze this same corpus of data and to explore what type of point of view these modal categories represent and how the texts in the corpus are shaded.

Corpus

GlobalBiz: The Art of Strategy. 02 Feb 2013

GlobalBiz: 2013 Look Ahead. 29 Dec 2012

The Innovator’s Dilemma. 03 Nov 2012

GlobalBiz: Emerging Markets. 15 Sept 2012

GlobalBiz: Two Views of Japan. 14 April 2012

All the interviews were downloaded from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/podcasts/series/worldbiz/all

References

Benveniste 1971: Е. Benveniste, Problems in General Linguistics. Coral Gables: University of Miami Press.

Ivamato 1998: N. Iwamаto, Modality and point of view in media discourse. Working Papers in Applied Linguistics, 9, 17-41.

Kornil 2009: B. Cornille, Evidentiality and epistemic modality. Functions of Language, 16:1, 44-62.

Lajons 1977: J. Lyons, Semantics II, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nuits 2001а: Ј. Nuyts, Subjectivity as an evidential dimension in epistemic modal expressions. Journal of Pragmatics, 3, 383-400.

Nuits 2001b: Ј. Nuyts, Epistemic Modality, Language, and Conceptualization. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Traugot 2010: E. C. Traugott, Revisiting Subjectification and Intersubjectification in Kristin Davidse, Lieven Vandelanotte, and Hubert Cuyckens (eds.) Subjectification, Intersubjectification and Grammaticalization. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Ferstrete 2001: J. C. Verstraete, Subjective and objective modality: Interpersonal and ideational functions in the English modal auxiliary system. Journal of Pragmatics, 33, 1505-1528.

Subjektivnost i intersubjektivnost u diskursu globalne ekonomije

Rezime: U ovm radu sagledavali smo primere subjektivne i intersubjektivne modalnosti sa ciljem da, analizom modalnih prideva i priloga, pomoćnih modalnih glagola i glagola mišljenja kojima se one ostvaruju u diskursu globalne ekonomije, saznamo da li govornici pretežno eksplicitno izražavaju svoje mišljenje ili teže da podele odgovornost sa grupom ljudi. U analizi korpusa, koji se sastoji od pet intervjua, korišćen je model koji je predložio Jan Nuits u knjizi „Epistemička modalnost, jezik i konceptualizacija“. Očekivanja su bila da će govornici dominantno upotrebljavati intersubjektivno modalizovane iskaze, ne bi li umanjili odgovornost za iskazivanje određenih stavova. Međutim, analizom je ustanovljeno da se govornici pretežno izražavaju subjektivno. Sveukupno, bilo je 258 primera subjektivno i 68 intersubjektivno modalizovanih iskaza. Međutim, u korpusu dominiraju primeri pomoćnih glagola, što ukazuje na činjenicu da su govornici kolebljivi i da ostavljaju prostor za druga tumačenja.

Ključne reči: subjektivna i intersubjektivna modalnost, modalni glagoli, modalni pridevi, modalni prilozi, glagoli mišljenja.

December 23rd, 2014 at 08:55

Opa, dakle KH počinje da taguje i na engleskom… Koliko vidim, Google Vas voli:))) Bravo. Ovo je već ozbiljna digitalna nauka…

February 5th, 2015 at 15:03

Kakva stručnost. Zaista, malo je na netu mogućnosti iščitavanja ovako stručnih tekstova… Svakako ne posebno atraktivno za širu publiku, ali za znalce iz oblasti – neprocenjivo… Uostalom, ima na ovom sajtu, čini mi se, dovoljno sjajnog materijala i za širi auditorijum.